The Alchemical Wedding of Christian Rosycross

Anno 1459, published in 1616 by Johann Valentin Andreae

Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7

Second Day

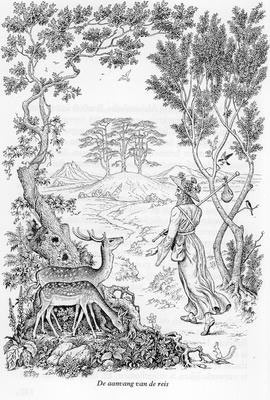

I had hardly got out of my cell into a forest when I thought the whole heaven and all the elements had already trimmed themselves in preparation for this wedding. For even the birds chanted more pleasantly than before, and the young fawns skipped so merrily that they made my heart rejoice, and moved me to sing; wherefore with a loud voice I thus began:

I had hardly got out of my cell into a forest when I thought the whole heaven and all the elements had already trimmed themselves in preparation for this wedding. For even the birds chanted more pleasantly than before, and the young fawns skipped so merrily that they made my heart rejoice, and moved me to sing; wherefore with a loud voice I thus began:

Rejoice dear bird

And praise thy Maker,

Raise bright and clear thy voice,

Thy God is most exalted,

Thy food he hath prepared for thee

To give thee in due season.

So be content therewith,

Wherefore shalt thou not be glad,

Wilt thou arraign thy God

That he hath made thee bird?

Wilt trouble thy wee head

That he made thee not a man?

Be still, he hath it well bethought

And be content therewith.

What do I then, a worm of earth

To judge along with God?

That I in this heaven's storm

Do wrestle with all art.

Thou canst not fight with God.

And whoso is not fit for this, let him be sped away

O Man, be satisfied

That he hath made thee not the King

And take it not amiss,

Perchance hadst thou despised his name,

That were a sorry matter :

For God hath clearer eyes that that

He looks into thy heart,

Thou canst not God deceive.

This I sang now from the bottom of my heart throughout the whole forest, so that it resounded from all parts, and the hills repeated my last words, until at length I saw a curious green heath, to which I betook myself out of the forest. Upon this heath stood three lovely tall cedars, which by reason of their breadth afforded excellent and desired shade, at which I greatly rejoiced. For although I had not hitherto gone far, yet my earnest longing made me very faint, whereupon I hastened to the trees to rest a little under them. But as soon as I came somewhat closer, I saw a tablet fastened to one of them, on which (as afterwards I read) in curious letters the following words were written:

"God save you, stranger! If you have heard anything concerning the nuptials of the King, consider these words. By us the Bridegroom offers you a choice between four ways, all of which, if you do not sink down in the way, can bring you to his royal court. The first is short but dangerous, and one which will lead you into rocky places, through which it will scarcely be possible to pass. The second is longer, and takes you circuitously; it is plain and easy, if by the help of the Magnet you turn neither to left nor right. The third is that truly royal way which through various pleasures and pageants of our King, affords you a joyful journey; but this so far has scarcely been allotted to one in a thousand. By the fourth no man shall reach the place, because it is a consuming way, practicable only for incorruptible bodies. Choose now which one you will of the three, and persevere constantly therein, for know whichever you will enter, that is the one destined for you by immutable Fate, nor can you go back in it save at great peril to life. These are the things which we would have you know. But, ho, beware! you know not with how much danger you commit yourself to this way, for if you know yourself to be obnoxious by the smallest fault to the laws of our King, I beseech you, while it is still possible, to return swiftly to your house by the way you came."

As soon as I read this writing all my joy nearly vanished again, and I who before sang merrily, began now inwardly to lament. For although I saw all the three ways before me, and understood that henceforward it was vouchsafed to me to choose one of them, yet it troubled me that if I went the stony and rocky way, I might get a miserable and deadly fall, or if I took the long one, I might wander out of it through byways, or be in other ways detained in the great journey. Neither could I hope that I amongst thousands should be the very one who should choose the royal way. I saw likewise the fourth before me, but it was so environed with fire and exaltations, that I did not dare draw near it by much, and therefore again and again considered whether I should turn back, or take any of the ways before me. I considered well my own unworthiness, but the dream still comforted me that I was delivered out of the tower; and yet I did not dare confidently rely upon a dream; whereupon I was so perplexed in various ways, that very great weariness, hunger and thirst seized me.

Whereupon I presently drew out my bread and cut a slice of it; which a snow-white dove of whom I was not aware, sitting upon the tree, saw, and therewith (perhaps according to her usual manner) came down. She betook herself very familiarly with me, and I willingly imparted my food to her, which she received, and so with her prettiness she again refreshed me a little. But as soon as her enemy, a most black raven, perceived it, he straightaway darted down upon the dove, and taking no notice of me, would force away the dove's food, and she could not guard herself otherwise than by flight. Whereupon they both flew together towards the south, at which I was so hugely incensed and grieved that without thinking what I did, I hastened after the filthy raven, and so against my will ran into one of the forementioned ways a whole field's length. And thus the raven having been chased away, and the dove delivered, I then first observed what I had inconsiderately done, and that I was already entered into a way, from which under peril of great punishment I could not retire. And though I had still wherewith in some measure to comfort myself, yet that which was worst of all to me was that I had left my bag and bread at the tree, and could never retrieve them. For as soon as I turned myself about, a contrary wind was so strong against me that it was ready to fell me. But if I went forward on the way, I perceived no hindrance at all. From which I could easily conclude that it would cost me my life if I should set myself against the wind, wherefore I patiently took up my cross, got up onto my feet, and resolved, since so it must be, that I would use my utmost endeavour to get to my journey's end before night.

Now although many apparent byways showed themselves, yet I still proceeded with my compass, and would not budge one step from the Meridian Line; howbeit the way was often so rugged and impassable, that I was in no little doubt of it. On this way I constantly thought upon the dove and the raven, and yet could not search out the meaning; until at length upon a high hill afar off I saw a stately portal, to which, not regarding how far it was distant both from me and from the way I was on, I hasted, because the sun had already hid himself under the hills, and I could see no abiding place elsewhere; and this verily I ascribe only to God, who might well have permitted me to go forward in this way, and withheld my eyes that so I might have gazed beside this gate.

To this I now made great haste, and reached it in so much daylight as to take a very competent view of it. Now it was an exceedingly royal beautiful portal, on which were carved a multitude of most noble figures and devices, every one of which (as I afterwards learned) had its peculiar signification. Above was fixed a pretty large tablet, with these words, "Procul hinc, procul ite profani" ("keep away, you who are profane"), and other things more, that I was earnestly forbidden to relate.

Now as soon as I came under the portal, there straightaway stepped forth one in a sky-coloured habit, whom I saluted in a friendly manner; and though he thankfully returned this salute, yet he instantly demanded of me my letter of invitation. O how glad was I that I had then brought it with me! For how easily might I have forgotten it (as it also chanced to others) as he himself told me! I quickly presented it, wherewith he was not only satisfied, but (at which I much wondered) showed me abundance of respect, saying, "Come in my brother, you are an acceptable guest to me"; and entreated me not to withhold my name from him. Now I having replied that I was a Brother of the Red-Rosy Cross, he both wondered and seemed to rejoice at it, and then proceeded thus: "My brother, have you nothing about you with which to purchase a token?" I answered that my ability was small, but if he saw anything about me he had a mind to, it was at his service. Now he having requested of me my bottle of water, and I having granted it, he gave me a golden token on which stood no more than these two letters, S.C., entreating me that when it stood me in good stead, I would remember him. After which I asked him how many had come in before me, which he also told me, and lastly out of mere friendship gave me a sealed letter to the second Porter.

Now having lingered some time with him, the night grew on. Whereupon a great beacon upon the gates was immediately fired, so that if any were still upon the way, he might make haste thither. But the way, where it finished at the castle, was enclosed on both sides with walls, and planted with all sorts of excellent fruit trees, and on every third tree on each side lanterns were hung up, in which all the candles were lighted with a glorious touch by a beautiful Virgin, dressed in sky-colour, which was so noble and majestic a spectacle that I yet delayed somewhat longer than was requisite. But at length after sufficient information, and an advantageous instruction, I departed friendlily from the first Porter.

On the way, I would gladly have known what was written in my letter, yet since I had no reason to mistrust the Porter, I forbare my purpose, and so went on the way, until I came likewise to the second gate, which though it was very like the other, yet it was adorned with images and mystic significations. On the affixed tablet was "Date et dabitur vobis" ("give and it shall be given unto you"). Under this gate lay a terrible grim lion chained, who as soon as he saw me arose and made at me with great roaring; whereupon the second Porter who lay upon a stone of marble woke up, and asked me not to be troubled or afraid, and then drove back the lion; and having received the latter which I gave him with trembling, he read it, and with very great respect said thus to me: "Now welcome in God's Name to me the man who for a long time I would gladly have seen." Meanwhile he also drew out a token and asked me whether I could purchase it. But having nothing else left but my salt, I presented it to him, which he thankfully accepted. Upon this token again stood only two letters, namely, S.M.

I was just about to enter into discourse with him, when it began to ring in the castle, whereupon the Porter counseled me to run, or else all the pains and labour I had hitherto undergone would serve to no purpose, for the lights above were already beginning to be extinguished. Whereupon I went with such haste that I did not heed the Porter, I was in such anguish; and truly it was necessary, for I could not run so fast but that the Virgin, after whom all the lights were put out, was at my heels, and I should never have found the way, had she not given me some light with her torch. I was moreover constrained to enter right next to her, and the gate was suddenly clapped to, so that a part of my coat was locked out, which I was verily forced to leave behind me. For neither I, nor they who stood ready without and called at the gate, could prevail with the Porter to open it again, but he delivered the keys to the Virgin, who took them with her into the court.

Meanwhile I again surveyed the gate, which now appeared so rich that the whole world could not equal it. Just by the door were two columns, on one of which stood a pleasant figure with this inscription, "Congratulor". The other, which had its countenance veiled, was sad, and beneath was written, "Condoleo". In brief, the inscriptions and figures were so dark and mysterious that the most dextrous man on earth could not have expounded them. But all these (if God permits) I shall before long publish and explain.

Under this gate I was again to give my name, which was this last time written down in a little vellum book, and immediately with the rest despatched to the Lord Bridegroom. It was here where I first received the true guest token, which was somewhat smaller than the former, but yet much heavier. Upon this stood these letters, S.P.N. Besides this, a new pair of shoes were given me, for the floor of the castle was laid with pure shining marble. My old shoes I was to give away to one of the poor who sat in throngs, although in very good order, under the gate. I then bestowed them upon an old man, after which two pages with as many torches conducted me into a little room.

There they asked me to sit down on a form, which I did, but they, sticking their torches in two holes, made in the pavement, departed and thus left me sitting alone. Soon after I heard a noise, but saw nothing, and it proved to be certain men who stumbled in upon me; but since I could see nothing, I had to suffer, and wait to see what they would do with me. But presently perceiving them to be barbers, I entreated them not to jostle me so, for I was content to do whatever they desired; whereupon they quickly let me go, and so one of them (whom I could not yet see) finely and gently cut away the hair round about from the crown of my head, but over my forehead, ears and eyes he permitted my ice-grey locks to hang. In this first encounter (I must confess) I was ready to despair, for inasmuch as some of them shoved me so forcefully, and yet I could see nothing, I could think nothing other but that God for my curiosity had suffered me to miscarry. Now these invisible barbers carefully gathered up the hair which was cut off, and carried it away with them.

After which the two pages entered again, and heartily laughed at me for being so terrified. But they had scarcely spoken a few words with me when again a little bell began to ring, which (as the pages informed me) was to give notice for assembling. Whereupon they asked me to rise, and through many walks, doors and winding stairs lit my way into a spacious hall. In this room was a great multitude of guests, emperors, kings, princes, and lords, noble and ignoble, rich and poor, and all sorts of people, at which I greatly marvelled, and thought to myself, 'ah, how gross a fool you have been to engage upon this journey with so much bitterness and toil, when (behold) here are even those fellows whom you know well, and yet never had any reason to esteem. They are now all here, and you with all your prayers and supplications have hardly got in at last'. This and more the Devil at that time injected, while I notwithstanding (as well as I could) directed myself to the issue.

After which the two pages entered again, and heartily laughed at me for being so terrified. But they had scarcely spoken a few words with me when again a little bell began to ring, which (as the pages informed me) was to give notice for assembling. Whereupon they asked me to rise, and through many walks, doors and winding stairs lit my way into a spacious hall. In this room was a great multitude of guests, emperors, kings, princes, and lords, noble and ignoble, rich and poor, and all sorts of people, at which I greatly marvelled, and thought to myself, 'ah, how gross a fool you have been to engage upon this journey with so much bitterness and toil, when (behold) here are even those fellows whom you know well, and yet never had any reason to esteem. They are now all here, and you with all your prayers and supplications have hardly got in at last'. This and more the Devil at that time injected, while I notwithstanding (as well as I could) directed myself to the issue.

Meanwhile one or other of my acquaintance here and there spoke to me: "Oh Brother Rosencreutz! Are you here too?"

"Yes (my brethren)," I replied, "the grace of God has helped me in too".

At which they raised mighty laughter, looking upon it as ridiculous that there should be need of God in so slight an occasion. Now having demanded each of them concerning his way, and finding that most of them were forced to clamber over the rocks, certain trumpets (none of which we yet saw) began to sound to the table, whereupon they all seated themselves, every one as he judged himself above the rest; so that for me and some other sorry fellows there was hardly a little nook left at the lowermost table.

Presently the two pages entered, and one of them said grace in so handsome and excellent a manner, that it made the very heart in my body rejoice. However, certain great Sr John's made but little reckoning of them, but jeered and winked at one another, biting their lips within their hats, and using other similar unseemly gestures. After this, meat was brought in, and although no one could be seen, yet everything was so orderly managed, that it seemed to me as if every guest had his own attendant. Now my artists having somewhat recreated themselves, and the wine having removed a little shame from their hearts, they presently began to vaunt and brag of their abilities. One would prove this, another that, and commonly the most sorry idiots made the loudest noise. Ah, when I call to mind what preternatural and impossible enterprises I then heard, I am still ready to vomit at it. In a word, they never kept in their order, but whenever one rascal here, another there, could insinuate himself in between the nobles, then they pretended to having finished such adventures as neither Samson nor yet Hercules with all their strength could ever have achieved: this one would discharge Atlas of his burden; the other would again draw forth the three-headed Cerberus out of Hell. In brief, every man had his own prate, and yet the greatest lords were so simple that they believed their pretences, and the rogues so audacious, that although one or other of them was here and there rapped over the fingers with a knife, yet they flinched not at it, but when anyone perchance had filched a gold-chain, then they would all hazard for the same.

I saw one who heard the rustling of the heavens. The second could see Plato's Ideas. A third could number Democritus's atoms. There were also not a few pretenders to the perpetual motion. Many a one (in my opinion) had good understanding, but assumed too much to himself, to his own destruction. Lastly, there was one also who found it necessary to persuade us out of hand that he saw the servitors who attended us, and would have persuaded us as to his contention, had not one of these invisible waiters reached him such a handsome cuff upon his lying muzzle, that not only he, but many more who were by him, became as mute as mice.

But it pleased me most of all, that all those of whom I had any esteem were very quiet in their business, and made no loud cry of it, but acknowledged themselves to be misunderstanding men, to whom the mysteries of nature were too high, and they themselves much too small. In this tumult I had almost cursed the day when I came here; for I could not behold but with anguish that those lewd vain people were above at the board, but I in so sorry a place could not rest in quiet, one of those rascals scornfully reproaching me for a motley fool.

Now I did not realise that there was still one gate through which we must pass, but imagined that during the whole wedding I was to continue in this scorn, contempt and indignity, which I had yet at no time deserved, either from the Lord Bridegroom or the Bride. And therefore (in my opinion) he should have done well to sort out some other fool than me to come to his wedding. Behold, to such impatience the iniquity of this world reduces simple hearts. But this really was one part of my lameness, of which (as is before mentioned) I dreamed. And truly the longer this clamour lasted, the more it increased. For there were already those who boasted of false and imaginary visions, and would persuade us of palpably lying dreams.

Now there sat by me a very fine quiet man, who often discoursed of excellent matters. At length he said, "Behold my brother, if anyone should now come who were willing to instruct these blockish people in the right way, would he be heard?"

"No, verily", I replied.

"The world," he said, "is now resolved (whatever comes of it) to be cheated, and cannot abide to give ear to those who intend its good. Do you see that same cocks-comb, with what whimsical figures and foolish conceits he allures others to him. There one makes mouths at the people with unheard-of mysterious words. Yet believe me in this, the time is now coming when those shameful vizards shall be plucked off, and all the world shall know what vagabond impostors were concealed behind them. Then perhaps that will be valued which at present is not esteemed."

Whilst he was speaking in this way, and the longer the clamour lasted the worse it was, all of a sudden there began in the hall such excellent and stately music such as I never heard all the days of my life; whereupon everyone held his peace, and waited to see what would become of it. Now in this music there were all the sorts of stringed instruments imaginable, which sounded together in such harmony that I forgot myself, and sat so immovable that those who sat by me were amazed at me; and this lasted nearly half an hour, during which time none of us spoke one word. For as soon as anyone at all was about to open his mouth, he got an unexpected blow, nor did he know where it came from. I thought since we were not permitted to see the musicians, I should have been glad to view just all the instruments they were using. After half an hour this music ceased unexpectedly, and we could neither see or hear anything more.

Presently after, a great noise began before the door of the hall, with sounding and beating of trumpets, shalms and kettle-drums, as majestic as if the Emperor of Rome had been entering; whereupon the door opened by itself, and then the noise of the trumpets was so loud that we were hardly able to endure it. Meanwhile (to my thinking) many thousand small tapers came into the hall, all of which themselves marched in so very exact an order as altogether amazed us, till at last the two aforementioned pages with bright torches entered the hall, lighting the way of a most beautiful Virgin, all drawn on a gloriously gilded triumphant self-moving throne. It seemed to me that she was the very same who before on the way kindled and put out the lights, and that these attendants of hers were the very same whom she formerly placed at the trees. She was not now, as before, in sky-colour, but arrayed in a snow-white glittering robe, which sparkled with pure gold, and cast such a lustre that we could not steadily look at it. Both the pages were dressed in the same manner (although somewhat more modestly). As soon as they came into the middle of the hall, and had descended from the throne, all the small tapers made obeisance before her. Whereupon we all stood up from our benches, yet everyone stayed in his own place. Now she having showed to us, and we again to her, all respect and reverence, in a most pleasant tone she began to speak as follows:

The King, my gracious lord

He is not far away,

Nor is his dearest bride,

Betrothed to him in honour.

They have now with the greatest joy

Beheld your coming hither.

Wherefore especially they would proffer

Their favour to each one of you,

And they desire from their heart's depth

That ye at all times fare ye well,

That ye have the coming wedding's joy

Unmixed with others' sorrow.

Hereupon with all her small tapers she courteously bowed again, and soon after began as follows:

Ye know what in the invitation stands :

No man hath been called hither

Who hath not got from God already

All gifts most beautiful,

And hath himself adorned aright

As well befits him here,

Though some may not believe it,

That any one so wayward be

That on such hard conditions

Should dare to make appearance

When he hath not prepared himself

For this wedding long before.

So now they stand in hope

That ye be well furnished with all good things,

Be glad that in such hard times

So many folk be found

But men are yet so forward that

They care not for their boorishness

And thrust themselves in places where

They are not called to be.

Let no knave be smuggled in

No rogue slip in with others.

They will declare right openly

That they a wedding pure will have,

So shall upon the morrow's morn

The artist's scales be set

Wherein each one be weighed

And found what he forgotten hath.

Of all the host assembled here

Who trusts him not in this

Let him now stand aside.

And should he bide here longer

Then he will lose all grace and favour

Be trodden underfoot,

And he whose conscience pricketh him

Shall be left in this hall today

And by tomorrow he'll be freed

But let him come hither never again.

But he who knows what is behind him

Let him go with his servant

Who shall attend him to his room

And there shall rest him for this day,

For he awaits the scales with praise

Else will his sleep be mighty hard.

Let the others make their comfort here

For he who goes beyond his means

'Twere better he had hid away.

And now the best from each be hoped.

As soon as she had finished saying this, she again made reverence, and sprung cheerfully into her throne, after which the trumpets began to sound again, which yet was not forceful enough to take the grievous sighs away from many. So they conducted her invisibly away again, but most of the small tapers remained in the room, and one of them accompanied each of us.

In such perturbation it is not really possible to express what pensive thoughts and gestures were among us. Yet most of us were resolved to await the scale, and in case things did not work out well, to depart (as they hoped) in peace. I had soon cast up my reckoning, and since my conscience convinced me of all ignorance, and unworthiness, I purposed to stay with the rest in the hall, and chose rather to content myself with the meal I had already taken, than to run the risk of a future repulse. Now after everyone had each been conducted into a chamber (each, as I since understood, into a particular one) by his small taper, there remained nine of us, and among the rest he who discoursed with me at the table too. But although our small tapers did not leave us, yet soon after an hour's time one of the aforementioned pages came in, and, bringing a great bundle of cords with him, first demanded of us whether we had concluded to stay there; when we had affirmed this with sighs, he bound each of us in a particular place, and so went away with our small tapers, and left us poor wretches in darkness.

Then some first began to perceive the imminent danger, and I myself could not refrain from tears. For although we were not forbidden to speak, yet anguish and affliction allowed none of us to utter one word. For the cords were so wonderfully made that none could cut them, much less get them off his feet. Yet this comforted me, that still the future gain of many a one who had now taken himself to rest, would prove very little to his satisfaction. But we by only one night's penance might expiate all our presumption. Till at length in my sorrowful thoughts I fell asleep, during which I had a dream. Now although there is no great matter in it, yet I think it not impertinent to recount it.

I thought I was upon a high mountain, and saw before me a great and large valley. In this valley were gathered together an unspeakable multitude of people, each of which had at his head a thread, by which he was hanged from Heaven; now one hung high, another low, some stood even almost upon the earth. But through the air flew up and down an ancient man, who had in his hand a pair of shears, with which he cut here one's, there another's thread.

I thought I was upon a high mountain, and saw before me a great and large valley. In this valley were gathered together an unspeakable multitude of people, each of which had at his head a thread, by which he was hanged from Heaven; now one hung high, another low, some stood even almost upon the earth. But through the air flew up and down an ancient man, who had in his hand a pair of shears, with which he cut here one's, there another's thread.

Now he that was close to the earth was so much more ready, and fell without noise, but when it happened to one of the high ones, he fell so that the earth quaked. To some it came to pass that their thread was so stretched that they came to the earth before the thread was cut. I took pleasure in this tumbling, and it gave my heart joy, when he who had over-exalted himself in the air about his wedding got so shameful a fall that it even carried some of his neighbours along with him. In a similar way it also made me rejoice that he who had all this while kept himself near the earth could come down so finely and gently that even the men next to him did not perceive it.

But being now in my highest fit of jollity, I was jogged unawares by one of my fellow captives, upon which I was awakened, and was very much discontented with him. However, I considered my dream, and recounted it to my brother, lying by me on the other side, who was not dissatisfied with it, but hoped that some comfort might be meant by it. In such discourse we spent the remaining part of the night, and with longing awaited the day.